By ITA Volunteer and Board Member Liz Bridges

In the US, many of our most revered routes trace trails created by the native peoples of this continent. In Idaho, the Shoshone, Blackfoot, Paiute, Nez Perce and others had long established trails that connected spring foraging areas with summer hunting grounds, fall fishing stations with winter quarters. Over time, trails put in place by native peoples became roads and well-known routes across our wildest mountain ranges and deepest river valleys.

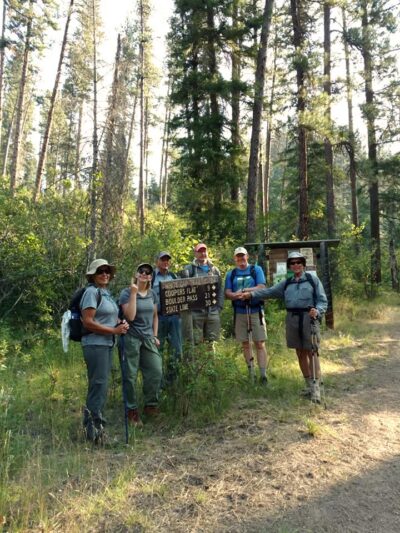

Five years ago, I joined a trail crew of volunteers with Idaho Trails Association to reopen a trail lost to time, located at the headwaters of the Selway River, one of our nation’s Wild and Scenic River corridors. ITA was created in 2010 by people of diverse backgrounds, all concerned about lost trails. The volunteer-driven group works closely with public land managers to identify trails that have become impassable, whether from deadfall, erosion, floods, overgrowth of brush or simply lack of use, and reopen them. I was the cook for the crew, looking for a summer adventure outside the confines of my 25 by 30-foot classroom, where I worked most of the year to bring our history to life for teens. Now I was entering a different classroom, and eager to enter a part of the landscape that was new to me. I arrived at the trailhead at Paradise Point campground, the end of the road off the Magruder Corridor, two days early, coolers clamped shut against the rising heat of summer, concerned that I was in the wrong spot or had the wrong time. Consulting my notes, I realized my time error, and settled in along the pristine river, reading, writing, and gathering my thoughts before the crew arrived.

It was through these rugged lands that the Nez Perce had fled, chased out of their verdant homelands in the Wallowas. I imagined them seeking the respite of a camp in a meadow below a bison horn shaped bluff, past which I had earlier driven. Near where I now sat, on a river eroded boulder in the middle of White Cap Creek, watching a blackbird perched on a thin branch that arched over the creek, many of the Nez Perce saw the Bitterroot Mountains for the last time.

The crew arrived, and along with them a string of the most magical animals I had ever seen: 8 glistening black pack mules, stock from Percheron mares crossed with Mammoth jack donkeys: huge, gentle, curious and kind, a “US” brand blazed on their haunches. The packer, Carl, was a quiet and unassuming man, tall, lanky, wearing Wrangler jeans, head shaded by a wide brimmed straw hat, partner of the hat I had earlier bought in Salmon from a cowboy poet haberdasher. I had no idea that the Forest Service still used mules, never having seen them in Colorado, in New England, and certainly not in the Apennines and Dolomites where I had grown up hiking. I was in awe and fascinated by the system of loading the mules with our coolers, tents, tools and supplies. Crates were packed, wrapped in “mantis”, capes of canvas, ropes were wound and knotted so that one pull would unravel the load, mules tethered with hand woven bites of rope, taut enough to tie tail to head harness, but loose enough to break should something go array on a trail.

We hiked in 9 miles and set up base camp beside a cabin originally built in the late 1800’s by bachelor fur trappers at Cooper Flat along White Cap Creek. The original cabin had burned years before, and this cabin, old still, replaced it. For some reason it had been spared destruction, and now served as a base for Forest Service operations, who had kindly permitted us to use it as our kitchen. Carl unloaded the mule string and left, to return in a week, and we set up tents, wash stations, tables, and laid out our tools: Pulaskis, loppers, crosscut saws and draw saws, which we would use to open the trail up to a ridgeline slightly south and east of our camp. The previous week, a different ITA crew, who we passed hiking out as we hiked in, worked on opening a different trail to Vance Lake, it, too, starting at the cabin at Cooper Flat.

The trail we were sent to open supposedly started at our camp, wended its way for a short while up Canyon Creek, and then up a sidehill of Peach Creek to a high ridge. Once on the ridge, the trail reportedly swept around the head of Canyon Creek to the highlands above Vance Lake. There was no trace of the trail from camp, and so we set out like hound dogs, sweeping back and forth across the sloping meadow, looking for openings in the already open Ponderosa pine forest, searching for old cut logs that would indicate past trail work, or faint traces of old treads. Climbing up on a shallow bench above Canyon Creek we began to find the evidence we sought, and set to work with loppers, cutting back an 8’ wide by 10’ tall path, wide enough and tall enough for the passage of a mounted horse, the standard the Forest Service works by in most areas.. Within short order, a trace of the old trail was seen dropping down to cross Canyon Creek, and once that was crossed, the trail began to reveal itself more clearly as the trees grew denser, the old cuts closer to one another.

I worked along with the crew for a while, but set a daily turnaround time of 2, to give me time to get back to camp, get appetizers ready and dinner going for the crew’s return, usually around 5 each afternoon. The week set up in a nice flow: I woke in the early dawn, warmed water for hand washing, got coffee brewing and breakfast ready, then helped someone in the crew set out fixings for lunch sandwiches. A crew member washed the dishes and then when they set out, I did my mis en place for the evening meal, cleaned up camp, organized camp, and then either set out on the trail to catch up to the crew, or read, wrote, and relaxed in the bee buzzing meadow. Usually I hiked up the trail, foraging ahead of the team first to give them an idea of the lay of the trail, then to count downed trees, and later, as they rose higher, to find a spring described in an old account of the trail, but long unused by people.

The higher I got, the bolder the birds grew. Unused to human companionship, a small flock of Western tanagers flitted overhead, accompanying me, warning the forest of my approach. The trail was exceptionally steep, and eschewed switchbacks, preferring the transhumance pattern I experienced in Corsica and in the Apennines, of getting from Point A to Point B in the straightest, fastest line, regardless the pitch of the slope. The birds, hearing my heavy breathing and the clack of my hiking sticks, which I tapped together periodically to warn huckleberry munching bears, were aptly warned of my approach and, apparently, took great joy in reprimanding me as I entered their territory. I reached a saddle and sat, and the tanagers took up guarding positions in neighboring trees. Across the Peach Creek drainage, I could see where successional fires had burned the forest, and could measure, to a certain extent, how long ago the forest had burned, by the differing heights of the canopies, and by the different color and patterns of the vegetation. The tanagers were quickly joined by a scolding mountain chickadee, who hazed me with its rapid fire, “Dzhee dzee dzee!”. Last to arrive at the ridge, a brazened goldfinch took offense at my straw hat and dive bombed its wide brim, swerving abruptly mid-air as I turned to see my miniature attacker.

Eventually I found the spring and also an old pair of wire framed glasses, twisted in the heat of an old forest fire that had blazed across the hillside. I counted the deadfall, at one point sixty downed trees in the space of a mile and made it to the ridge and a pyramidal peak, from which I could see the brilliant granite of the White Cap Mountains beckoning me on, and on and on. Mindful of the time, I turned to the valley, left my fine feathered friends in a fickle, and made it back to camp to make the cutlets, salad and two Dutch oven bread puddings, one soaked in the last of my whiskey, for the crew’s return. This summer I will go back, and perhaps will be a part of the crew that succeeds in opening the trail to Vance Lake, into which I plan on plunging. I hope my bird friends will be there to greet me. I will need to bring my hat so that they can recognize me.

Rediscovering a trail, and restoring it, connects me not just to the land, but to the people who were there before me, connects me to the animals, connects me to what matters most deeply to my soul. In rediscovering a trail, I discover a landscape and carve a connection with a transitory world. The lost trail I worked, above Cooper Flat, has engraved itself in my heart and has connected me with the past and future. It beckons and calls and I will return, with a friend or two or eight, delighting in the travail and trail, in the heart of Idaho and this country’s wilderness.

This year for Idaho Gives from May 2-5, ITA is raising funds to save lost trails. Learn more here!

What a great read & great writing. My mind could imagine being right there in that place. It’s always good to connect with nature in this crazy world we live in today.